No future for European rice market

-says Sankar

Stabroek News

July 16, 2004

Guyana's rice industry hangs in the balance. (Ken Moore photo)

There is no market in Europe for local rice producers, who should look to exploit more viable options in the Caribbean and in South America, suggests Caribbean Rice Association (CRA) Chairman, Beni Sankar.

"The market is dead because no matter what we do we will not get the right price..." says Sankar, who laments that large European importers are now paying much less than they should.

"The price being offered by Europe, because of the monopoly situation, is very low... our prices in Europe should be much higher," he told Stabroek Business in a recent interview.

However, General Secretary of the Guyana Rice Producers' Association (GRPA), Dharamkumar Seeraj does not believe the market is completely lost, although he concedes it will not be there in the long-term.

"Europe is not the future... but it is not dead for us," he notes, agreeing that there is need to develop alternative markets before the remaining preferential ones are phased out.

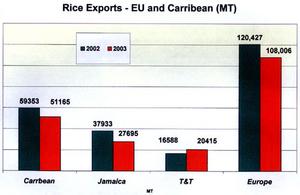

Rice Exports - EU and Caribbean

Over half of all Guyana's rice exports still go to European Union markets, where the country still has preferential access as part of the African-Caribbean-Pacific (ACP) group of countries. Under European Commission (EC) regulations, rice exports from ACP countries enter the EU market subject to a quota system. ACP exports are also charged a rate of duty lower than the rate on rice from other countries.

The system allows for 125,000 tonnes whole grain and 20,000 tonnes of broken rice to be exported directly from ACP countries to the EU.

An additional 35,000 tonnes of whole grain can be exported if it is processed overseas and would qualify through the Other Countries and Territories (OCT) route. Guyana exports in excess of 100,000 tonnes of whole grain rice to the EU annually and fills the bulk of the ACP and OCT quotas.

The ACP direct route quota of husked rice equivalent is divided up, and import licences are issued by the EC three times a year to European rice importers. Importers are required to pay a security deposit of Euro 120 per tonne of the licence they receive.

EU system hurts suppliers

But Sankar believes the system is disadvantageous to exporters, who are left at the mercy of large buyers who have a monopoly on the market and dictate prices. Indeed, most of the country's rice is imported by just two importers, according to government records.

Also, ACP whole grain and broken rice exports are levied a duty that is equal to 35% of the tariff levied on third country rice imports applied to products from Most Favoured Nations such as the USA and Australia.

Before a quota system was implemented in 1997, the bulk of Guyana's rice went to Europe through the OCT route, which is duty free. But with the introduction of the system, most rice exports enter now through the ACP direct route.

"The levy dropped from 50% to 35%. As the levy is going down, the price [paid by importers] is going down. It shouldn't be like that, it should be the opposite," says Sankar who feels that the current arrangements have led to what he calls a buyer's market.

Seeraj says the prices that are being dictated are equivalent to those exporters receive in the alternative markets of Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica.

"We were getting $400 a tonne in 96-97, today we are getting half of that, but the consumers are paying more for rice."

Both Sankar and Seeraj said export arrangements with the EU are being examined by the ACP/EU Joint Working Group on Rice, set up in January 2000 under the Cotonou agreement.

In this forum, Guyana and Suriname are said to be very active

in a campaign to get decision-makers to create a more market-friendly trading environment for exporters.

They said the Working Group, which is to meet in Brussels in a little more than a week, will be looking to totally remove the licence system and give the quota directly to the producers.

Nevertheless, Sankar feels that the EU recognises that there is no longer room for the region's imports.

He believes this to be one of the reasons behind the EU's $24M Euro grant to Cariforum countries to make the industry more competitive.

"I have no problem as long as they try to make us more competitive because we are now competing against heavily subsidised rice..." Sankar says.

Guyana recently signed an accord to access 11.7M Euros from the grant, for resource development and the marketing of the rice sector.

Sankar says the Caricom market is for the taking and even at the most recent meeting of the Council for Trade and Economic Development (COTED), it was noted that the regional industry has the potential to satisfy domestic requirements.

Going South for new markets

Sankar also believes there are also viable markets in some South and Central America countries such as Brazil, Venezuela and Peru.

He points out that there is already a Paddy Purchase Agreement worked out with Brazil that allows Guyana to export up to 10,000 tonnes of rice duty-free.

He says his company is in the process of exporting to Brazil, but describes the process as slow. He adds that some companies have also been examining the feasibility of exporting 'south' and says it is an option worth exploring.

Seeraj is in total agreement about capturing the regional market, but has not completely ruled out Europe, including possible niche markets there.

"We go there because we have a preferential market but those are going to be phased out and, like it or not, the reality of the day is that the developed countries are going to keep subsidising in different forms and ways and in some cases support is going to increase," he adds.

But he says in the interim, Guyana has to try to capture markets in Caricom and the Caribbean and develop those available in the South America. And he thinks that the markets are so vast that production capabilities will be under strain to supply them.

Seeraj says there are markets in Brazil for rice, though logistics are likely obstacles.

He adds that there are new markets in the Caribbean, including the Dominican Republic as well as traditional markets in Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica and Haiti where Guyana is increasing its foothold. He says over 4000 tonnes of the last crop were exported to the Dominican Republic, while Jamaica still remains Guyana's single-largest Caricom buyer.

"In these markets, our people are becoming more and more aggressive..." he says, citing the development of packaging the parboiled exports.

"We [are] sending rice even to places like Colombia, which are not traditional markets."

Seeraj, nevertheless thinks that the next three and a half years

should be used by small countries like Guyana to develop niche markets, noting that there is a market preference for extra-long grain rice.

"We still have at least three and a half years [before WTO trade liberalisation kicks in] to establish preference for our rice, we can still trade with Europe, but we will have to diversify."

Seeraj worries about the lack of alternative markets, especially in the Caribbean, where he says Guyana is losing out to heavily-subsidised imports from the US.

Monitoring key to protecting Caricom

"The US is killing us here in our own backyard which is one of the reasons for the Regional Monitoring Mechanism..."

This was one of the issues addressed at the 17th Meeting of the Council for Trade and Economic Development (COTED) held in Trinidad and Tobago recently.

Before the meeting, Sankar had criticised countries shirking their obligations under the Rice Monitoring Mechanism, which he felt imperils the industry.

Caricom is Guyana's second largest market, but the country is losing out to extra-regional imports which are said to account for more than 50% of trade.

The Rice Monitoring Mechanism obligates member states to provide production, export and import data to the Caricom Secretariat by the July 31 and January 31 of each year. The information is to be collated and analysed, then fed back to the participating states and COTED to craft policies and strategies for the industry.

Sankar had urged Caricom to get tough on the offending states, such as Jamaica, who are responsible for significant subsidised rice imports.

Since then, Belize, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago have submitted data under the mechanism.

Sankar says countries are now providing proper information, after what he describes as a lot of hassle.

"I hope the trend will continue... [we] will get the information and we will be able to see what is happening in the industry."

Based on the submissions, it was found that St. Vincent - which imports from extra-regional sources to supplement stock for its packaging plant - did not apply the Common External Tariff (CET) on recent imports and a waiver was not granted.

Sankar says the issue was raised at the COTED meeting, but there were no representatives from the island to offer an explanation.

He says countries which buy from the island would be encouraging the continuation of this practice, while COTED has agreed to look at importation loopholes. It has also agreed to take stronger steps against member states that breach the Rice Monitoring Mechanism. (Andre Haynes)