Mutiny aboard a slave ship

In the trading language of the West African coast, a factory was a place where European and African goods could be stored under the control of Europeans who lived there and conducted trade. These goods could be exchanged for humans. In addition, large compounds called barracoons were maintained for holding humans until they embarked for the Atlantic voyage. Large factories frequently acquired territorial rights and were to become the keystone of colonial domination.

Sugar, manufactured from the Asian sugar-cane plant which had been introduced into southern Europe by the Arabs, was regarded as an exotic luxury in those times and fetched very high prices in Europe. Sugar-cane cultivation moved gradually to southern Spain and Portugal in the 14th century, reaching the Atlantic islands of Madeira by the middle of the 15th century. By 1485, Portugal had seized and settled the islands in the Gulf of Guinea - Fernão do Po, O Principe and São Tomé - where the rich volcanic soil and high rainfall facilitated the cultivation of tropical crops. Here, the Portuguese introduced sugar cane from the Madeira Islands.

Cultivation was highly labour-intensive, particularly at harvest time when the cane, once cut, must be collected quickly and milled. Abundant labour was provided by Africans captured from the nearby mainland and enslaved on the islands. From there, sugar cultivation was transferred to Brazil which had been claimed by Pedro Alvares Cabral (1500) and had become Portuguese property.

European colonisation of the Americas was the next step in the evolution of the Atlantic trade. Christopher Columbus claimed the territories he came upon for the Crown of Castille, believing that he had reached the fabulous Indies. Attempts at settlement started from his second voyage (1493) when sugar, already being grown in the Spanish Atlantic (Canary) Islands, was taken to the Caribbean islands.

The enslavement of indigenous Amerindians under the Spanish repartimiento system was halted as early as 1501. Instead, the encomienda system was introduced but this only slowed, and did not stop, the decimation of the Amerindian population by disease, overwork, hunger and murder at the hands of the European colonists. Having killed off most of the Amerindians, settlers sought new sources of labour in Africa. The first shipment of Africans took place from Seville to Hispaniola (Española) in 1505 and, five years later, direct shipments from Africa to America started.

The next step in the growth of the Atlantic trade was the Roman Catholic Pope's demarcation of spheres of exploration and exploitation between the two Catholic Iberian countries - Spain and Portugal. After Portugal's capture of Ceuta from the Moslem Moors in 1415, the papacy was petitioned and a series of bulls was promulgated by Pope Nicholas V and, later, by his successor Pope Calixtus III.

In the most important of these - Dum Diversas (18 June 1452) - the King of Portugal was authorised to "attack, conquer and subdue the Saracens, pagans and other unbelievers, to capture their goods and territories and "…reduce their persons to perpetual slavery…" In Romanus Pontifex (8 January 1455), the King of Portugal was authorised to subdue and convert pagans found anywhere between Morocco and the Indies. And, in Inter Caetera (13 March 1456), the Papacy conceded "…spiritual jurisdiction of all regions conquered by the Portuguese now or in the future…" from Cape Bojador and Nun by way of Guinea and beyond to the Indies.

The effect of these bulls was to provide papal sanction for the religious and racial oppression of Africans by Christian Europeans and to permit, for a few decades at least, the unimpeded exploitation of Africa by the Portuguese to the exclusion of the Spanish and other Europeans. It was on these foundations and on the trade in captive Africans that the Portuguese built their power in Africa that prevailed for 500 years until they were expelled by liberation wars in Angola, Guinea Bissau and Mozambique in the 1970s.

Western Europeans - from Britain, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Prussia and Sweden - flocked to the Caribbean during the 17th century, seizing islands on which they established plantations. The Spanish had already decimated the Amerindian people thus the colonists' choice of labour was limited to the employment of European settlers or indentured servants, or of Africans who had been captured and enslaved. The colonists' demand for cheap labour, therefore, provided the main stimulus for European enslavement of Africans and was eventually to turn the trickle of involuntary immigrants into a torrent.

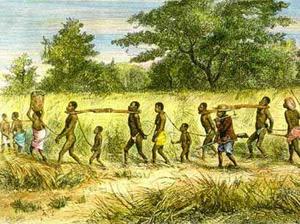

Exodus

During the first century after the Atlantic trade started, only small numbers of captives were transported to the New World. The Portuguese had implanted sugar-cane cultivation successfully in Bahia and Pernambuco in North-East Brazil and, by 1580, sugar production had already surpassed that of their Atlantic islands. The enslaved labour force was estimated at 13,000 to 15,000.

The Spanish had also introduced sugar-cane in their sphere of America and, by 1518, production was sufficiently advanced to demand and receive authority for the direct shipment of 1,000 Africans to the Caribbean. The first asiento was granted in 1595 to a Portuguese, Pedro Gomes Reinel, to transport 38,250 Africans at a rate of 4,250 per annum.

Political events in Europe, however, accelerated the tempo of economic and demographic change in America and Africa. Dutch merchants had been the principal distributors in Northern Europe of Asian, African and American tropical produce already flowing from the overseas empires of Spain and Portugal. But the Netherlands revolted against Habsburg domination and, when Philip II King of Spain became King of Portugal as well in 1580, he closed Iberian ports to Dutch ships in order to punish and weaken the rebels.

The merchants and government of the United Netherlands responded by creating the Dutch East India Company (1602) and the Dutch West India Company (1621) "…to engage directly in commercial ventures on the Atlantic and Indian Ocean, and to attack and destroy Spanish and Portuguese power on them…" The Dutch East India Company crippled Portuguese power in the Indian Ocean in the first decade of the 17th century and, between 1637 and 1642, the Dutch West India Company succeeded in seizing all the major Portuguese trading posts on the West Coast of Africa.

The Dutch also captured north-eastern Brazil where the plantation production of sugar and other tropical goods was the dominant economic activity. These plantations were already entirely dependent on African labour and this was the reason that the (Dutch) company's governor in Brazil, Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen, started a campaign to capture Portuguese posts on the West African Coast. Portugal was able to regain its independence from Spain, however, and expelled the Dutch from Brazil in 1654.

The Dutch then turned their attention and technology to the Guianas and the Caribbean colonies where, with their knowledge of cultivation, control of transportation, capacity to supply captive labour and access to financial credit, they were able to establish the slave-based cultivation of sugar. It is arguable, therefore, that it was these Dutch initiatives, rather than the early Portuguese ventures, "…which led to the incorporation of tropical Africa into the dynamic world trading system dominated by Western Europeans."

Although sugar had been introduced by the Spanish a century and a half earlier, it was the Dutch who initiated the true 'sugar revolution' in the Caribbean. The revolution was confined to Barbados at first but such was the wealth to be gained that all of the English and French islands followed suit, changing from Europeanised settler societies to Africanised slave economies.

At this stage, English and other European countries founded national trading companies to compete with the Dutch and Portuguese in trafficking in humans from West Africa. The English had entered the trade under John Hawkins since 1562 but the old Company of Adventurers of London was replaced by the Royal African Company, chartered on 27 September 1672. The establishment of joint-stock companies was an important commercial innovation which enabled the king to assume "suzerainty over all those areas actually held by the company in West Africa." Thus, the royal charter became the 'legal' origin of the claims to the territories that eventually became British colonies in West Africa.

Chronicles

France, Sweden, Denmark and Prussia (Brandenburg), encouraged by the Dutch success in destroying the Portuguese monopoly and by the British efforts at establishing a national slave-trading company and lured by the prospects of profits to be gained from trafficking in humans, followed suit and created their own trading companies. This precipitated fierce competition to acquire territory to erect coastal forts and posts which became the fulcrum of the trade in Africa and the focus of envy and rivalry among slave-trading states in the 17th and 18th centuries.

France established its base on an island in the mouth of the Senegal River, built the town of St Louis and dominated the area from Senegal to the Gambia. Portugal retained control of the rivers and off-shore islands south of the Gambia. Britain controlled the coast from Sierra Leone to the Sherbro islands. The Netherlands established forts from Accra to Axim where they strongly challenged the British, Swedes, Danes and Prussians, the last three being eventually eliminated from the trade.

Europeans hardly penetrated far inland, prevented from doing so by the coastal Africans in order that they could extract as much profit as possible from the trade. Collaboration with African chiefs was essential, some prepared to trade their prisoners of war for European manufactures such as alcohol, cloth, firearms, tools and utensils. It is for this reason and the convenience of shipping that major slaving stations were located on the coastland and not in the hinterland.

The transport of goods manufactured in Europe to be traded in Africa and, in turn, the transport of Africans to the Caribbean and the Americas to be traded for tropical products which were then taken back to Europe, came to constitute a 'great circuit' of commerce, better known as the 'triangular trade.' This provided a triple stimulus to British industry - captives were acquired in Africa by exchanging them for European manufactured goods. They were taken to the plantations of the New World where they produced tropical goods, including cotton, molasses, rum, sugar and tobacco, which were shipped to Europe where they were processed, creating new industries there.

By stimulating shipping, manufacturing, marketing and production of agricultural goods, the triangular trade came to constitute a large volume of overall international economic transactions during the period 1451-1870. It was not only that the human traffic was profitable in itself but also that it became indispensable to the development of Caribbean agriculture which provided support for the American colonies. An Atlantic economy, embracing the Americas, Africa and Europe came into existence, supplanting the Mediterranean economy as the major hub of Western commerce.

Scores of ports and cities, hundreds of industries, thousands of ships and millions of people all around the Atlantic became involved in the trade. The volume of the flow of captives from Africa could best be assessed by the number of ships involved. When by 1760 Great Britain had become the world's supreme slave-trading state, 146 ships with a capacity of 36,000 captives sailed for Africa. Eleven years later (1771), the number had increased to 190 ships with a capacity of 47,000 captives. During the period 1782-1786, 130 ships each with an average of 396 captives arrived in Jamaica. During the last quarter of a century of the British trade (1782-1808) in fact, 681 ships carried 220,985 Africans to Jamaica alone.

The increased infusion of captive Africans into the plantation economies of the Caribbean was indispensable to their prosperity. But, before they reached their destinations, the captives had to survive the torture of the route from Africa to America known as the 'middle passage.' On embarkation, the captives were stripped of their garments. They were then sorted, the men being shackled in pairs and the women - regarded as fair prey for the sailors - and children might be allowed to wander about the ship by day, but were confined by night. Conditions were congested and cramped for all persons aboard - crew and human cargo alike.

Owing to the limited space allocated to each captive, said to be "smaller than a coffin" in the stifling, stinking holds where infectious diseases spread quickly and easily, mortality was the greatest challenge. West African ports were the crossroads of continental diseases, European crews importing gonorrhoea, syphilis, small pox and measles, and Africans contributing a variety of tropical fevers, dysentery, yaws and elephantiasis. Physiological disease was often supplemented by psychological disorders which had been precipitated by the trauma of their violent capture.

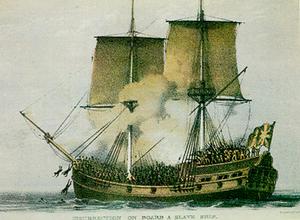

In the event of emergencies such as food shortages or epidemics on the voyage, captives might be murdered by simply being jettisoned from the ships. The level of mortality arising out of disease and murder could be high although health practices and efficiency improved towards the end of the 18th century. The threat of mutiny, however, was ever-present. Although armed crew members or soldiers were usually on board, mutinies were frequent, especially in one period (1750-1788) when Liverpool merchants tried to save money by reducing crews. During the period 1699-1745, 55 mutinies were reported on slaving ships and references were made to more than 100 others.

The maintenance of the crew and captives was another problem. The trans-Atlantic voyage could be as short as three weeks on the route from the Gambia to Barbados or as long as three months from Angola to Virginia. For English ships travelling to Jamaica from the Gold Coast during the years 1791-1798, the average sailing time was 56 days (eight weeks). From time to time, such as when the ships were becalmed in the Doldrums, driven off-course or damaged by hurricanes, an extraordinary amount of provisions could be used up or lost before the journey's end. In such emergencies, captains "…simply jettisoned part of the cargo" in order to have fewer mouths to feed.

Management practices on the Atlantic crossing varied slightly from state to state. The British were regarded as cruel, but the Americans were much worse because their ships were lightly-manned with small crews, necessitating harsher conditions and stricter security measures against the captives. Dutch ships were regarded as the most commodious since they "…were carefully planned for the trade." Despite such differences, European practices in the Atlantic trade were similar.

The Atlantic crossing was the most vital and the most vulnerable link in the chain of transactions of the Atlantic trade. Under the mercantile system, European states attempted to establish exclusive ownership of territories and total control of commercial activities with them. Mercantilist theory held that colonies should export primary commodities to, import manufactured goods from, and transport cargoes in vessels of, the metropolitan countries which owned them. The trade in captive Africans was an essential element of the mercantile system.

Numbers

The first significant surge in the number of African captives transported to the Caribbean had occurred as a consequence of the successful implantation of sugar-cane cultivation as a plantation, as opposed to peasant, enterprise before the middle of the 17th century. Barbados, the leading producer, possessed 20,000 enslaved Africans by 1650; Jamaica became the world's largest sugar producer with 45,000 by 1700; but Saint Domingue surpassed Jamaica and already had an enslaved population of 230,000 by 1750.

Most of the Caribbean islands were brought under sugar-cane cultivation by the 1780s by which time the French and British territories together possessed a population of over 1,000,000 enslaved and freed Africans. In the former British colonies of North America where cotton became the dominant plantation crop, there were over 757,000 enslaved and freed Africans by 1790, at the end of the colonial period. In Spanish America, plantation economies developed after the exploitation of precious minerals subsided and, by the end of the 18th century, the islands and mainland contained about 2,000,000 enslaved and freed Africans.

After the overthrow of the slave regime in St Domingue, substantial sugar and coffee interests shifted to Cuba and Brazil which experienced booms in the production of these two commodities, created largely by African labour. When slavery still flourished in Brazil in 1872, the African population was 5,700,000 most of whom were still enslaved. Cuba had an enslaved population of 399,000 by 1861.

During the first century and a half (approximately) and after sugar was introduced into the British West Indies, about 1,500,000 Africans were transported into the islands, four-fifths of whom were retained for labour and the remainder re-exported. It is estimated that a similar number was carried to British North America and foreign countries without being entered in Caribbean port records. In fact, few correct records exist anywhere and it is impossible to determine with a reasonable degree of accuracy the number of Africans who were seized and who survived and were transported across the Atlantic to be sold during the 400 years of the trade.

It has been variously suggested that altogether about 50,000,000 African captives were involved at the most, and fewer than 10,000,000 survived, to be sold to planters, at the least. The figure of 50,000,000, which might be considered conservative, was calculated by estimating the captives killed in raids and wars; the trek in coffles to the coast; the confinement in barracoons there; death from exposure to disease; mortality on the ships taking them across the Atlantic; and death from the shock of 'seasoning' after they arrived at their destinations and

No records were likely to have existed in the circumstances in which they were captured. Numerous other unrecorded deaths doubtless occurred as a result of shipwrecks, sinkings, storms and hostile (piratical) action at sea. Interlopers and privateers striving to break the monopolies of the chartered companies of national governments were known to have traded Africans in the Americas on their own account. For various reasons, captives taken to some colonies such as Barbados were re-exported elsewhere.

Taken as a whole, therefore, it could be said that about 50,000,000 Africans were victims of the Atlantic trade. Other sources have suggested that about 15,000,000 living Africans reached the Americas but this figure was not arrived at scientifically. By the technique of using a partial estimate plus a multiplier factor, and of studying the evidence of port entries, shipping records, enslaved populations (in America), exports (from Africa), and contemporary estimates (from ships' captains, travellers and officials), some writers arrived at a figure of 9,566,100 captives, which has gained some acceptance.

Abolition

The European Atlantic trade in captive Africans was terminated at various times during the 19th century. The legal process started with Denmark (1804); Britain (1807), Sweden (1813), the Netherlands (1814) and France (1818) followed. The Iberian states - Spanish Cuba and Portuguese Brazil - continued to import captives until well after 1860. The Iberians, historically, "…were the first to start the slave trade and the last to quit."

Despite the apparent vitality and profitability of the Atlantic trade, its foundations were already being undermined as early as the middle of the 18th century. The demise of the old mercantile system and the rise of the new industrial capitalism were the most important factors which led directly to the abolition of the Atlantic trade in Britain in 1807. But they were not the sole causes; other important factors were the effects of warfare, particularly the Seven Years' War (1756-1763); the expansion of the British Empire into India; the impact of the Revolution in St Domingue; and the humanitarian activism of abolitionists in the British Parliament.

The Seven Years' War severely weakened France and Britain, its two main belligerents. The French monarchy's attempts to raise revenue in the wake of that war led directly to the outbreak of the French Revolution which destroyed the monarchy. The British government's attempts to raise revenue from its American colonies similarly precipitated the American Revolution and the loss of those colonies. The war nevertheless enabled Britain to conquer Canada and defeat the French in India; these two vast territories provided new sources of raw materials and markets for its manufactured goods.

With the French Revolution, the genie of liberté was out of the bottle and several short-lived revolts destabilised the colonies of the West Indies. The revolution in the French colony of St Domingue shattered the myth of European superiority and shook the entire system of slavery. British troops based in Jamaica invaded St Domingue in September 1793, remaining there until August 1798, in an attempt to restore the enslavement of Africans and to protect the European colonists, among other things.

The English were badly beaten, suffering thousands of casualties and were forced to withdraw in ignominy. Spanish and French armies sent against the revolutionaries in St Domingue, similarly, were destroyed. The lessons of the humiliating defeats of European soldiers by former enslaved Africans and the establishment of Haiti as an independent state in 1804 were not lost on British parliamentarians when they came to consider the continuation of the Atlantic trade a few years later.

The industrial revolution - a period of accelerated advance in private capitalism, large-scale production for definite markets and improvements in transport - brought into existence not only a new class of industrial capitalists based on the ownership of fixed capital, plant and machinery, but also an entirely new market-driven economic system. This emergent economy relied on new sources of raw materials and large markets which, in comparison to the vast East Indies and other Asian and African territories, the small islands of the West Indies could not furnish.

The humanitarian debates in the British Parliament that led to the abolition of the trade were nothing more than the funeral rites for a system that had already become dysfunctional and was dying. It used to be thought that the decision of Great Britain, the most active slave-trading state in the world, to outlaw the Atlantic trade was largely the result of the efforts of a group of reformers. Indeed, their efforts in the British Parliament were instrumental in securing the passage of the Abolition Act in March 1807 but the motives for abolition went far beyond mere humanitarian concerns.

In the final analysis, the Atlantic trade in which millions of people were forcibly moved across the Atlantic from Africa to the Americas indelibly influenced the economies, cultures and character of the entire western world. The trade in Africans from the 15th century had, by the 19th, helped to make the Atlantic area the world's dominant commercial and economic zone.

For Africa, generations of warfare, the haemorrhaging of the fittest part of its populations and the partition of its native states by Europeans impoverished much of the Guinea Coast. For much of the Americas, particularly Brazil, the Caribbean and Southern USA, the descendants of the victims of the Atlantic trade now constitute substantial and influential portions of the populations, many workers today being still employed as praedial labourers as their forefathers had been. For Europe, the systems of colonialism and mercantilism under which the trade thrived, thrust Western Europe into its present position of economic pre-eminence in the world.

The question remains whether a quantitative study of such a massive movement of humans, however accurately calculated, could adequately explain the qualitative changes which took place in the Atlantic continents. The academic debate over the numbers involved in the trade, however, cannot diminish the responsibility that Europeans must bear for the Atlantic trade in captive Africans, the greatest crime against humanity.